Many northern peoples seek the right to self-determination and its actualization by controlling their fate or course of action or achieving political independence. Policymakers and leaders often focus on the legal implications of this, but there is a big difference between de jure self-determination – the legal right to exercise political independence – and de facto self-determination – the capacity to do so.

What does this have to do with nursing, you might rightly wonder. The history of nursing in northern communities has been one of regularly importing southern professionals to the community to conduct primary and preventive care. Vaccinations, prenatal and postnatal care, emergency care and chronic illness management are among the many critically important tasks these nurses perform in communities.

But the practice has also institutionalized southern/urban healthcare systems in northern communities, with all the benefits but also the baggage they bring. It can perpetuate external, and sometimes inappropriate, methods of healthcare; entrench geographic and cultural power hierarchies; and can be costly to maintain – hiring and retention bonuses to try to mitigate a perennial shortage in nursing staff, and travel and housing costs to import non-resident nurses add up, and are worsened by turnover and burnout. (This is no reflection on the nurses themselves. They typically provide excellent care that would otherwise go undelivered, frequently under challenging conditions.)

Registered nurses are the dominant healthcare professionals found in most northern healthcare systems, and resident in almost every community. Increasingly, they are northerners themselves, an important part of achieving self-determination.

Learn Where You Live

Like most things, building a northern nursing workforce is easier said than done. In almost all Arctic countries (but not yet in Russia), registered nurses must complete a university degree, buttressed by hundreds of hours of clinical practice. But there are many challenges to recruiting nursing students from northern communities. They are frequently women with children to care for or with other family responsibilities, and they often have to leave home for their studies, typically traveling hundreds of kilometers to the south, to larger urban centers. These duties, compounded by the expense of education and the barriers imposed by cultural differences, often prevent students from even applying.

To address the shortage of registered nurses in northern communities, there is a move afoot to offer nursing education in a distributed, decentralized or distance education manner. Roughly a dozen universities and colleges are now offering courses at satellite campuses and through online, videoconference and even robotic technologies. Since 2015, they have been sharing best practices in delivering high-quality – and contextually relevant – nursing education through a University of the Arctic network on Northern Nursing Education.

Institute on Circumpolar Health

These initiatives include opportunities to study abroad that bring nursing students together to learn from each other and about best practices in northern nursing practice and healthcare. Last year, a small pilot program saw two northern Saskatchewan students study in Yakutsk with local Russian students. This summer, twelve nursing students from Lapland (Finland), Finnmark (Norway), Akureyri (Iceland), Yakutsk (Russia), Greenland and the northern regions of the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan, Manitoba and British Columbia gathered at the University of Saskatchewan. During the 10-day program, they discussed their communities’ similarities and differences, and visited four northern Saskatchewan communities to learn about their approaches to community health and well-being. It is often remarked that such opportunities for study abroad are “life-changing”; this was no exception.

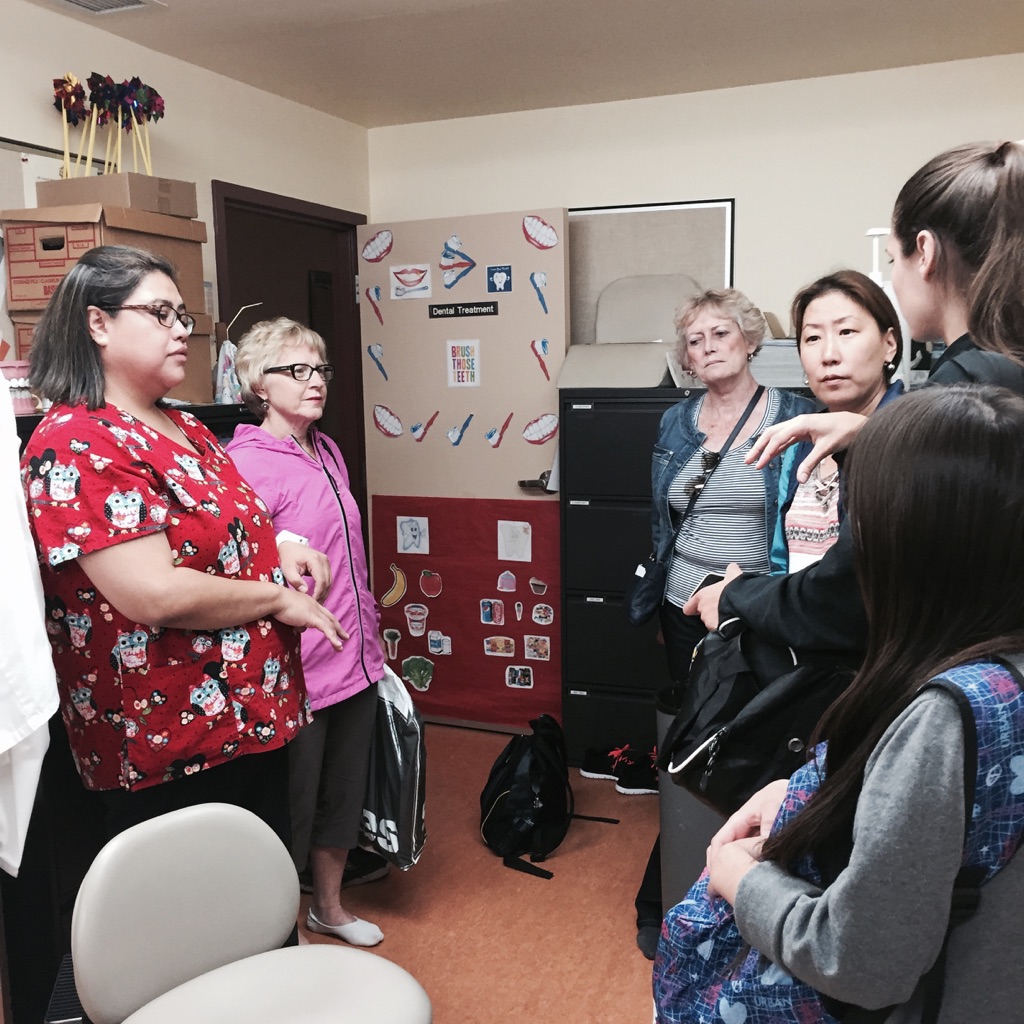

Recent northern nursing graduate Janet McKenzie discusses the community of Stanley Mission’s (Amachewespimawin) nursing station services with students from Finland and Russia. (Heather Exner-Pirot)

The students quickly found similarities in their home regions and the challenges they faced in doing their jobs. Access to healthcare, distance to services and poor weather are challenges, of varying degrees, everywhere. Northern nurses often work in isolation and have huge responsibility. For all the students, mental health issues were pervasive and under-addressed within the communities they covered. Some regions were doing more than others, however, in addressing them by reducing the stigma associated with suicide, depression, alcohol and drug abuse, and surviving sexual abuse.

At the same time, the students found that the health challenges in northern Canada, Greenland and Russia, where there are large indigenous populations, large distances and less economic development, were greater than in the Nordic region. What we call the social determinants of health – including food insecurity, poor and overcrowded housing, violence and trauma – had a noticeable impact on healthcare needs.

Wellness in Practice

We visited four diverse communities in northern Saskatchewan – La Ronge, the region’s administrative center; Stanley Mission, a reserve community of the Lac La Ronge Indian Band; and Pinehouse and Ile-à-la-Crosse, two Métis communities (the Métis are one of Canada’s Aboriginal peoples) – to better understand their concepts of health and wellness. Overall this part of the province is the size of Norway but has only 40,000 residents, 86 percent of whom are indigenous, distributed across 45 communities.

The biggest takeaway for the students was not that these communities were sad or poor or desperate, as we so often describe them, implicitly or explicitly, when calculating health indicators and gaps. Instead, the students saw strong, resilient and proud communities, with leaders who were making concrete efforts to “reclaim” the things that had been lost during the era and aftermath of colonization and residential schools. “We were misled into waiting for someone from the outside to come in to the community and fix everything,” declared one of our hosts, “but we are not waiting anymore. We are fixing things ourselves.” For example, one community had arranged to host monthly community meetings of all community organizations – the school, police, health clinic, village office, daycare, social workers – to proactively address problems as they arise. Likewise, the students were warned not to see their role as nurses fixing their patients, but as empowering people to fix themselves.

Students receiving teaching from elders in the healing room at the La Ronge Health Centre. (Lorna Butler)

The students had strong cultural experiences – some attended their first sweat (a purification ceremony) – and received warm hospitality. We ate walleye and white fish, blueberries and wild rice, and, over the course of 10 days, six kinds of bannock, the baking-soda biscuit popularized during the Canadian fur trade in the 18th and 19th centuries.

On the whole, the experience was a powerful reminder that while the North is different, it is not worse off. “You are so lucky to live here,” some of the participants told the student from northern Saskatchewan after we had enjoyed her community’s natural, historical and cultural endowments. “I hadn’t seen my community from that perspective before,” she later remarked.

While northerners have unique health challenges, they also have the tools and power to solve them. Having northern nurses deliver healthcare in their own communities, alongside colleagues from other cultures, is an important part of accomplishing that.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Arctic Deeply.